All releases uploaded on the CiDAR Africa platform automatically falls under our standard distribution license from the moment of upload. For more details, please see our contract form page and contract terms.

GLOBAL MUSIC TRADITIONS: Episode 4

Samba and resistance: How rhythm became rebellion

All throughout history, from time immemorial, music has been a medium of self-expression and creativity, but also more importantly, a tool for retaliation or revolutionary action against oppression.

From diss tracks to satires, Rap to Hip-hop, jazz and blues, music has reflected cultural, social, economic and political realities, as well as the important shifts in society, and has been an organum for change, for the fight for freedom.

In fact, a number of musical artistes like Gil Scott Heron, Bob Dylan, J cole, Sam Cooke and many others have argued that music holds a purpose and ability to address real, social issues. On a deeper note, other artistes like Fela and Bob Marley used their music intentionally as a voice for change and to fight against systemic, political oppression. Fela specifically believed that music was a weapon for rebellion, as he put it “Music is the weapon. Music is the weapon of the future”.

This value of music holds a different kind of intensity for the Afro community as a whole. Having been victim to all kinds of oppression from slavery, to the battle of the civil rights movement, enduring racism and prejudice till today, music was the one place we could speak and celebrate our excellence, the one thing we communed with that connected us together. It was the one thing we created that they couldn’t take away and it became the important thing we fought to keep.

Today we talk about one of the greatest forms of rhythm that became the face of rebellion for entire communities of people in Europe; Samba Music.

SAMBA MUSIC

Samba is often imagined today as the glittering soundtrack of Carnival music in Rio, with dazzling costumes and endless fast-paced drums. But its origins tell a far deeper, more complicated story, one rooted in struggle, survival, and the unshakable spirit of Afro-Brazilian communities. Samba grew from the margins of society, a rhythm once criminalized, into Brazil’s national symbol, and at every stage, it carried the DNA of resistance.

The word Samba, is a broad term for Brazilian rhythms that originated in the Afro Brazilian communities of Bahia (a state in Brazil), in the late 19th century and early 20th century, as well as communities in Rio.

Having its roots in Brazilian folk traditions, especially those linked to the primitive rural samba of the colonial and imperial periods, it is considered one of the most important cultural phenomena in Brazil

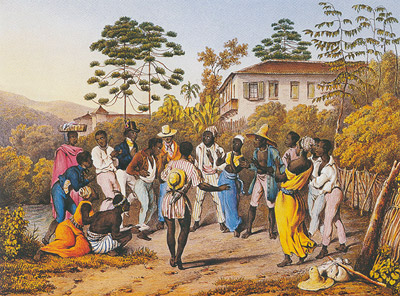

Samba first came about as a way of representing or designating a popular dance style, a "batuque-like circle dance”. Batuque itself was a general term for Afro brazilian practices in the 19th century that included music, dance and combat games, as well as religion. Usually filled with drums and was more a cultural activity where everybody gathered around, like on Sunday evenings.

In the corners of Bahia, the batuque dance evolved into different forms of Samba, while the combat game was gradually absorbed by the capoeira (Brazilian martial art and games, that is spiritual, acrobatic, and music-filled). Then, in Rio Grande, bautuque became the general term of Afro-Brazilian religion.

If there’s one thing Brazilians are known fo,r it’s having serious fun through music and rhythm, like beats are a part of their system, blood, bones, spirit and culture. Feet twisting and spinning. The enslaved Afro-Brazilians would gather around for batuque festivities, the only fun they could make given the excruciating circumstances. To the Brazilian elites, these Batuque gatherings and their samba African rhythms symbolized a form of disorder, immorality, and the poverty of Black communities in Rio’s favelas. They held onto that derogatory ideology that anything black was dirty and uncouth.

And later on, in the year 1822, the police began to shut down these batuque gatherings but despite their attempts at repression, the Brazilian slaves persisted and continued their gatherings in quieter secret meetings at the outskirts where the police was sure not to reach. Sometimes when the police came they fought back, sometimes they skedaddled to live another day. Scattering and recovening somewhere else. It was both dangerous and thrilling.

And so doing best what we know how, being our authentic selves, Practicing samba in public became in many ways, a political act. It was an assertion of dignity and identity in the face of discrimination.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that Samba became a genre of its own with its own two feet. It develop with developed with the migrants from Bahia who moved to Rio and São Paul, From the neighborhood of Estácio (named after Estacio de sa, The founder of Rio de Janerio, a Portuguese soldier and officer) and soon extended to Oswaldo Cruz and other parts of Rio through its commuter rail.

By the early 20th century, samba began to migrate from backyards (quintais) into the streets of Carnival. The creation of the first samba schools (escolas de samba), such as Deixa Falar in 1928, provided it structure and visibility. Samba schools weren’t just music groups; they were community organizations, run by people from marginalized neighborhoods, that taught children, supported families, and turned cultural pride into spectacle. Through parades, samba schools staged grand stories about slavery, injustice, African heritage, and the lives of the poor for the whole city to see.

Politically, samba took on a double role. In the 1930s, during Getúlio Vargas’ Estado Novo regime, samba was co-opted as a tool of nationalism. Vargas promoted a sanitized form of samba-exaltação (exaltation samba), which praised Brazil’s beauty, unity, and progress. This helped samba gain mainstream recognition as “the music of Brazil.”

But underneath this state-approved image, samba’s grassroots traditions carried a parallel resistance. While Vargas’ samba painted Brazil as a harmonious paradise, samba schools used lyrics, costumes, and allegories to critique inequality, racism, and government corruption, cleverly disguising social commentary in rhythm and pageantry.

Through decades of repression, samba remained a voice of those excluded from Brazil’s official story. It became the rhythm of the working-class Black neighborhoods of Rio, São Paulo, and beyond. Each drum ensemble was not just a performance but a declaration: We are here. We belong. Our culture will not be erased.

Today, samba is globally recognized as Brazil’s cultural treasure, but it is important to remember its roots in resistance. The Carnival parades watched by millions now are the descendants of gatherings once chased by police. The elaborate costumes are echoes of African masquerades, culture dance and energy. The joyful addictive rhythm carries centuries of pain, resilience, and defiance. Samba shows that music can be more than just entertainment it can be survival, memory, and a tool for liberation.

Samba music was the voice the Brazilians had to say, no you cannot take that away too. It was a fight for freedom, individuality and expression, a right to possess, what was rightfully theirs.